Theology of the Icon a Large Number of Works About Sacred Christian Art

An icon (from the Greek εἰκών eikṓn 'prototype, resemblance') is a religious piece of work of art, well-nigh usually a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, the Roman Catholic, and certain Eastern Catholic churches. They are not only artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion".[i] The virtually mutual subjects include Christ, Mary, saints and angels. Although especially associated with portrait-style images concentrating on ane or two main figures, the term also covers almost religious images in a variety of artistic media produced past Eastern Christianity, including narrative scenes, usually from the Bible or the lives of saints.

Icons are nearly normally painted on wood panels with egg tempera, only they may as well be cast in metal, carved in stone, embroidered on cloth, done in mosaic or fresco work, printed on newspaper or metal, etc. Comparable images from Western Christianity can be classified as "icons", although "iconic" may also be used to draw a static style of devotional paradigm. In the Greek language, the term for icon painting uses the same word equally for "writing", and Orthodox sources ofttimes translate information technology into English as icon writing.[2]

Eastern Orthodox tradition holds that the production of Christian images dates back to the very early days of Christianity, and that information technology has been a continuous tradition since then. Modernistic academic fine art history considers that, while images may have existed earlier, the tradition tin can be traced back only as far every bit the tertiary century, and that the images which survive from Early on Christian art frequently differ profoundly from subsequently ones. The icons of afterwards centuries can be linked, ofttimes closely, to images from the fifth century onwards, though very few of these survive. Widespread destruction of images occurred during the Byzantine Iconoclasm of 726–842, although this did settle permanently the question of the appropriateness of images. Since and then, icons have had a neat continuity of style and subject, far greater than in the icons of the Western church. At the same time there accept been change and development.

History [edit]

Emergence of the icon [edit]

A rare ceramic icon; this one depicts Saint Arethas (Byzantine, 10th century)

Pre-Christian religions had produced and used art works.[four] Statues and paintings of various gods and deities were regularly worshiped and venerated. It is unclear when Christians took upwards such activities. Christian tradition dating from the 8th century identifies Luke the Evangelist as the first icon painter, merely this might not reflect historical facts.[5] A general supposition that early Christianity was generally aniconic, opposed to religious imagery in both theory and practice until nigh 200, has been challenged by Paul Corby Finney's assay of early Christian writing and textile remains (1994). This distinguishes three different sources of attitudes affecting early on Christians on the consequence: "first that humans could accept a direct vision of God; second that they could not; and, third, that although humans could see God they were best advised not to look, and were strictly forbidden to correspond what they had seen". These derived respectively from Greek and Nigh Eastern infidel religions, from Aboriginal Greek philosophy, and from the Jewish tradition and the Old Testament. Of the three, Finney concludes that "overall, Israel's disfavor to sacred images influenced early Christianity considerably less than the Greek philosophical tradition of invisible deity apophatically defined", so placing less emphasis on the Jewish groundwork of virtually of the first Christians than well-nigh traditional accounts.[6] Finney suggests that "the reasons for the not-appearance of Christian art before 200 have nothing to do with principled aversion to art, with other-worldliness, or with anti-materialism. The truth is simple and mundane: Christians lacked state and capital. Art requires both. As presently as they began to learn land and capital, Christians began to experiment with their own distinctive forms of art".[7]

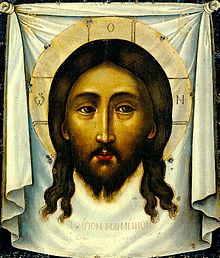

Aside from the legend that Pilate had made an image of Christ, the quaternary-century Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Church building History, provides a more than substantial reference to a "showtime" icon of Jesus. He relates that King Abgar of Edessa (died c. fifty CE) sent a alphabetic character to Jesus at Jerusalem, asking Jesus to come up and heal him of an illness. This version of the Abgar story does non mention an image, but a later account plant in the Syriac Doctrine of Addai (c. 400 ?) mentions a painted epitome of Jesus in the story; and even later, in the 6th-century account given by Evagrius Scholasticus, the painted image transforms into an image that miraculously appeared on a towel when Christ pressed the cloth to his wet confront.[8] Further legends relate that the cloth remained in Edessa until the 10th century, when information technology was taken past Full general John Kourkouas to Constantinople. It went missing in 1204 when Crusaders sacked Constantinople, but by and so numerous copies had firmly established its iconic type.

The fourth-century Christian Aelius Lampridius produced the earliest known written records of Christian images treated similar icons (in a pagan or Gnostic context) in his Life of Alexander Severus (xxix) that formed part of the Augustan History. According to Lampridius, the emperor Alexander Severus ( r. 222–235), himself not a Christian, had kept a domestic chapel for the veneration of images of deified emperors, of portraits of his ancestors, and of Christ, Apollonius, Orpheus and Abraham. Saint Irenaeus, (c. 130–202) in his Against Heresies (ane:25;6) says scornfully of the Gnostic Carpocratians:

They besides possess images, some of them painted, and others formed from different kinds of material; while they maintain that a likeness of Christ was made by Pilate at that time when Jesus lived among them. They crown these images, and set them up along with the images of the philosophers of the world that is to say, with the images of Pythagoras, and Plato, and Aristotle, and the rest. They have likewise other modes of honouring these images, after the same mode of the Gentiles [pagans].

On the other paw, Irenaeus does not speak critically of icons or portraits in a full general sense—only of certain gnostic sectarians' utilize of icons.

Another criticism of image veneration appears in the non-canonical 2nd-century Acts of John (generally considered a gnostic work), in which the Apostle John discovers that ane of his followers has had a portrait fabricated of him, and is venerating information technology: (27)

... he [John] went into the bedroom, and saw the portrait of an old human crowned with garlands, and lamps and altars set before information technology. And he called him and said: Lycomedes, what exercise you mean by this matter of the portrait? Can it be one of thy gods that is painted here? For I see that you are still living in heathen manner.

Later on in the passage John says, "But this that you have now done is childish and imperfect: you lot have drawn a dead likeness of the dead."

At least some of the hierarchy of the Christian churches still strictly opposed icons in the early on quaternary century. At the Spanish not-ecumenical Synod of Elvira (c. 305) bishops ended, "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they do not go objects of worship and adoration".[9]

Bishop Epiphanius of Salamis, wrote his letter 51 to John, Bishop of Jerusalem (c. 394) in which he recounted how he tore downward an paradigm in a church building and admonished the other bishop that such images are "opposed ... to our religion".[10]

Elsewhere in his Church History, Eusebius reports seeing what he took to be portraits of Jesus, Peter and Paul, and also mentions a bronze statue at Banias / Paneas under Mountain Hermon, of which he wrote, "They say that this statue is an epitome of Jesus" (H.E. 7:eighteen); farther, he relates that locals regarded the paradigm every bit a memorial of the healing of the adult female with an issue of blood by Jesus (Luke viii:43–48), because information technology depicted a continuing man wearing a double cloak and with arm outstretched, and a woman kneeling before him with artillery reaching out equally if in supplication. John Francis Wilson[xi] suggests the possibility that this refers to a pagan bronze statue whose true identity had been forgotten; some[ who? ] have idea information technology to represent Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing, but the description of the standing figure and the woman kneeling in supplication precisely matches images found on coins depicting the bearded emperor Hadrian ( r. 117–138) reaching out to a female person figure—symbolizing a province—kneeling before him.

When asked by Constantia (Emperor Constantine'due south half-sis) for an epitome of Jesus, Eusebius denied the request, replying: "To depict purely the man form of Christ before its transformation, on the other mitt, is to break the commandment of God and to fall into infidel error."[12] Hence Jaroslav Pelikan calls Eusebius "the male parent of iconoclasm".[1]

After the emperor Constantine I extended official toleration of Christianity within the Roman Empire in 313, huge numbers of pagans became converts. This period of Christianization probably[ original enquiry? ] saw the use of Christian images became very widespread among the true-blue, though with great differences from heathen habits. Robin Lane Trick states[13] "By the early 5th century, we know of the ownership of private icons of saints; by c. 480–500, we can be sure that the inside of a saint's shrine would exist adorned with images and votive portraits, a practice which had probably begun earlier."

When Constantine himself ( r. 306–337) apparently converted to Christianity, the majority of his subjects remained pagans. The Roman Purple cult of the divinity of the emperor, expressed through the traditional burning of candles and the offering of incense to the emperor'south image, was tolerated[ by whom? ] for a period because information technology would have been politically dangerous to attempt to suppress it.[ citation needed ] Indeed, in the 5th century the courts of justice and municipal buildings of the empire all the same honoured the portrait of the reigning emperor in this way. In 425 Philostorgius, an allegedly Arian Christian, charged the Orthodox Christians in Constantinople with idolatry considering they however honored the epitome of the emperor Constantine the Great in this way. Dix notes that this occurred more than a century before nosotros find the starting time reference to a similar honouring of the epitome of Christ or of His apostles or saints, only that it would seem a natural progression for the image of Christ, the King of Heaven and Globe, to exist paid like veneration as that given to the earthly Roman emperor.[14] Notwithstanding, the Orthodox, Eastern Catholics, and other groups insist on explicitly distinguishing the veneration of icons from the worship of idols past pagans.[fifteen]

Theodosius to Justinian [edit]

After adoption of Christianity as the only permissible Roman state religion under Theodosius I, Christian art began to change not only in quality and sophistication, but also in nature. This was in no small part due to Christians being complimentary for the first fourth dimension to express their faith openly without persecution from the state, in addition to the faith spreading to the not-poor segments of lodge. Paintings of martyrs and their feats began to appear, and early writers commented on their lifelike effect, ane of the elements a few Christian writers criticized in pagan art—the power to imitate life. The writers mostly criticized pagan works of fine art for pointing to fake gods, thus encouraging idolatry. Statues in the circular were avoided as beingness too close to the principal creative focus of pagan cult practices, as they have connected to be (with some small-scale-scale exceptions) throughout the history of Eastern Christianity.

Nilus of Sinai (d. c. 430), in his Letter to Heliodorus Silentiarius, records a miracle in which St. Plato of Ankyra appeared to a Christian in a dream. The Saint was recognized because the young man had frequently seen his portrait. This recognition of a religious apparition from likeness to an image was too a characteristic of pagan pious accounts of appearances of gods to humans, and was a regular topos in hagiography. One critical recipient of a vision from Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki plain specified that the saint resembled the "more ancient" images of him—presumably the 7th-century mosaics still in Hagios Demetrios. Another, an African bishop, had been rescued from Arab slavery by a young soldier called Demetrios, who told him to go to his house in Thessaloniki. Having discovered that most young soldiers in the city seemed to be called Demetrios, he gave upward and went to the largest church in the city, to detect his rescuer on the wall.[16]

During this period the church began to discourage all non-religious human images—the Emperor and donor figures counting as religious. This became largely effective, and so that nigh of the population would simply always see religious images and those of the ruling class. The word icon referred to any and all images, not just religious ones, simply in that location was barely a need for a separate word for these.

Luke's portrait of Mary [edit]

It is in a context attributed to the 5th century that the first mention of an image of Mary painted from life appears, though earlier paintings on catacomb walls acquit resemblance to modern icons of Mary. Theodorus Lector, in his 6th-century History of the Church ane:1[17] stated that Eudokia (wife of emperor Theodosius Ii, d. 460) sent an image of the "Mother of God" named Icon of the Hodegetria from Jerusalem to Pulcheria, girl of Arcadius, the former emperor and male parent of Theodosius II. The paradigm was specified to have been "painted by the Apostle Luke."

Margherita Guarducci relates a tradition that the original icon of Mary attributed to Luke, sent by Eudokia to Pulcheria from Palestine, was a big circular icon only of her head. When the icon arrived in Constantinople it was fitted in as the head into a very large rectangular icon of her holding the Christ kid and it is this composite icon that became the one historically known as the Hodegetria. She further states another tradition that when the concluding Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin Ii, fled Constantinople in 1261 he took this original circular portion of the icon with him. This remained in the possession of the Angevin dynasty who had it also inserted into a much larger image of Mary and the Christ child, which is presently enshrined above the high altar of the Benedictine Abbey church building of Montevergine.[eighteen] [19] Unfortunately this icon has been over the subsequent centuries subjected to repeated repainting, so that it is difficult to determine what the original epitome of Mary'south face would have looked like. However, Guarducci also states that in 1950 an ancient prototype of Mary[20] at the Church of Santa Francesca Romana was determined to be a very exact, but contrary mirror prototype of the original circular icon that was made in the 5th century and brought to Rome, where information technology has remained until the present.[21]

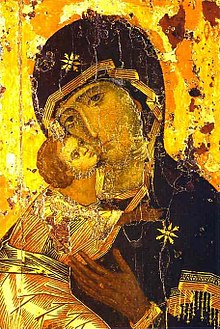

In afterward tradition the number of icons of Mary attributed to Luke would greatly multiply;[22] the Salus Populi Romani, the Theotokos of Vladimir, the Theotokos Iverskaya of Mount Athos, the Theotokos of Tikhvin, the Theotokos of Smolensk and the Black Madonna of Częstochowa are examples, and another is in the cathedral on St Thomas Mountain, which is believed to be one of the 7 painted past St. Luke the Evangelist and brought to India by St. Thomas.[23] Ethiopia has at least vii more.[24] Bissera V. Pentcheva concludes, "The myth [of Luke painting an icon] was invented in order to support the legitimacy of icon veneration during the Iconoclastic controversy" [8th and 9th centuries, much subsequently than well-nigh fine art historians put it]. Past claiming the being of a portrait of the Theotokos painted during her lifetime by the evangelist Luke, the iconodules "fabricated evidence for the apostolic origins and divine approval of images."[1]

In the flow before and during the Iconoclastic Controversy, stories attributing the creation of icons to the New Testament catamenia greatly increased, with several apostles and even the Virgin herself believed to have acted every bit the creative person or commissioner of images (too embroidered in the case of the Virgin).

Iconoclast flow [edit]

There was a standing opposition to images and their misuse within Christianity from very early times. "Whenever images threatened to gain undue influence inside the church, theologians take sought to strip them of their power".[25] Further, "in that location is no century between the fourth and the eighth in which there is not some evidence of opposition to images even inside the Church".[26] Nonetheless, pop favor for icons guaranteed their connected being, while no systematic apologia for or against icons, or doctrinal authorization or condemnation of icons however existed.

The use of icons was seriously challenged past Byzantine Purple authorisation in the eighth century. Though past this time opposition to images was strongly entrenched in Judaism and Islam, attribution of the impetus toward an iconoclastic movement in Eastern Orthodoxy to Muslims or Jews "seems to have been highly exaggerated, both past contemporaries and past mod scholars".[27]

Though significant in the history of religious doctrine, the Byzantine controversy over images is non seen as of primary importance in Byzantine history. "Few historians still hold it to have been the greatest issue of the period..."[28]

The Iconoclastic Catamenia began when images were banned past Emperor Leo III the Isaurian quondam between 726 and 730. Nether his son Constantine V, a council forbidding epitome veneration was held at Hieria most Constantinople in 754. Image veneration was later reinstated by the Empress Regent Irene, nether whom another council was held reversing the decisions of the previous iconoclast council and taking its title every bit Seventh Ecumenical Council. The council anathemized all who concord to iconoclasm, i.eastward. those who held that veneration of images constitutes idolatry. Then the ban was enforced again by Leo V in 815. And finally icon veneration was decisively restored by Empress Regent Theodora in 843.

From and then on all Byzantine coins had a religious image or symbol on the opposite, usually an image of Christ for larger denominations, with the head of the Emperor on the obverse, reinforcing the bond of the state and the divine lodge.[16]

Acheiropoieta [edit]

The tradition of acheiropoieta ( ἀχειροποίητα , literally "not-made-by-paw") accrued to icons that are alleged to have come up into existence miraculously, not by a human painter. Such images functioned as powerful relics besides as icons, and their images were naturally seen as particularly authoritative every bit to the true advent of the bailiwick: naturally and peculiarly because of the reluctance to take mere homo productions every bit embodying anything of the divine, a commonplace of Christian deprecation of man-made "idols". Like icons believed to exist painted straight from the live subject, they therefore acted as important references for other images in the tradition. Abreast the developed fable of the mandylion or Prototype of Edessa was the tale of the Veil of Veronica, whose very name signifies "true icon" or "true image", the fear of a "false image" remaining strong.

Stylistic developments [edit]

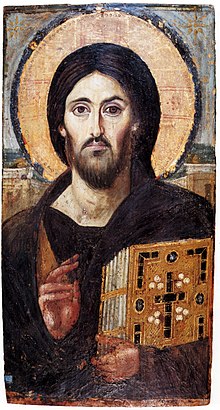

Although there are earlier records of their use, no console icons earlier than the few from the 6th century preserved at the Greek Orthodox Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt survive,[29] as the other examples in Rome take all been drastically over-painted. The surviving evidence for the earliest depictions of Christ, Mary and saints therefore comes from wall-paintings, mosaics and some carvings.[30] They are realistic in appearance, in contrast to the later stylization. They are broadly like in manner, though frequently much superior in quality, to the mummy portraits done in wax (encaustic) and establish at Fayyum in Egypt. As we may guess from such items, the first depictions of Jesus were generic rather than portrait images, more often than not representing him as a beardless young homo. It was some time earlier the earliest examples of the long-haired, bearded confront that was later to become standardized as the image of Jesus appeared. When they did begin to appear there was still variation. Augustine of Hippo (354–430)[31] said that no 1 knew the appearance of Jesus or that of Mary. However, Augustine was non a resident of the Holy Land and therefore was non familiar with the local populations and their oral traditions. Gradually, paintings of Jesus took on characteristics of portrait images.

At this time the mode of depicting Jesus was not yet uniform, and there was some controversy over which of the two most common icons was to exist favored. The beginning or "Semitic" course showed Jesus with curt and "frizzy" hair; the 2d showed a bearded Jesus with pilus parted in the middle, the manner in which the god Zeus was depicted. Theodorus Lector remarked[32] that of the ii, the one with short and frizzy pilus was "more authentic". To support his assertion, he relates a story (excerpted by John of Damascus) that a pagan commissioned to paint an epitome of Jesus used the "Zeus" class instead of the "Semitic" form, and that as punishment his easily withered.

Though their development was gradual, we tin can date the total-diddled appearance and general ecclesiastical (as opposed to simply popular or local) acceptance of Christian images as venerated and miracle-working objects to the 6th century, when, as Hans Belting writes,[33] "we showtime hear of the church'due south use of religious images". "As we achieve the second half of the sixth century, we find that images are attracting straight veneration and some of them are credited with the performance of miracles".[34] Cyril Mango writes,[35] "In the mail service-Justinianic period the icon assumes an ever increasing role in popular devotion, and there is a proliferation of miracle stories connected with icons, some of them rather shocking to our eyes". However, the earlier references by Eusebius and Irenaeus indicate veneration of images and reported miracles associated with them equally early on equally the 2nd century.

Symbolism [edit]

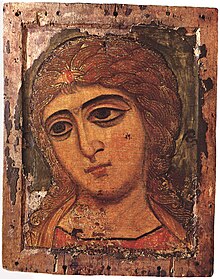

In the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy, and of the Early Medieval West, very little room is made for creative license. Nearly everything within the epitome has a symbolic aspect. Christ, the saints, and the angels all take halos. Angels (and often John the Baptist) have wings because they are messengers. Figures take consequent facial appearances, agree attributes personal to them, and utilize a few conventional poses.

Colour plays an important role as well. Aureate represents the radiance of Heaven; red, divine life. Blue is the colour of human life, white is the Uncreated Light of God, only used for resurrection and transfiguration of Christ. If y'all wait at icons of Jesus and Mary: Jesus wears red undergarment with a blueish outer garment (God become Homo) and Mary wears a blueish undergarment with a cherry overgarment (human was granted gifts past God), thus the doctrine of deification is conveyed by icons. Messages are symbols as well. Nigh icons contain some calligraphic text naming the person or effect depicted. Fifty-fifty this is often presented in a stylized manner.

Miracles [edit]

Our Lady of St. Theodore, a 1703 re-create of the 11th-century icon, following the same Byzantine "Tender Mercy" type as the Vladimirskaya above.

In the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition there are reports of particular, wonderworking icons that exude myrrh (fragrant, healing oil), or perform miracles upon petition by believers. When such reports are verified by the Orthodox bureaucracy, they are understood as miracles performed past God through the prayers of the saint, rather than existence magical properties of the painted woods itself. Theologically, all icons are considered to exist sacred, and are miraculous by nature, being a means of spiritual communion betwixt the heavenly and earthly realms. Nevertheless, it is not uncommon for specific icons to exist characterised as "miracle-working", meaning that God has chosen to glorify them past working miracles through them. Such icons are often given particular names (especially those of the Virgin Mary), and fifty-fifty taken from metropolis to city where believers get together to venerate them and pray earlier them. Islands like that of Tinos are renowned for possessing such "miraculous" icons, and are visited every year by thousands of pilgrims.

Eastern Orthodox teaching [edit]

The Eastern Orthodox view of the origin of icons is generally quite dissimilar from that of almost secular scholars and from some in gimmicky Roman Catholic circles: "The Orthodox Church maintains and teaches that the sacred epitome has existed from the kickoff of Christianity", Léonid Ouspensky has written.[36] Accounts that some not-Orthodox writers consider legendary are accepted as history inside Eastern Orthodoxy, because they are a role of church tradition. Thus accounts such equally that of the miraculous "Image Not Made by Hands", and the weeping and moving "Female parent of God of the Sign" of Novgorod are accepted every bit fact: "Church Tradition tells united states, for example, of the beingness of an Icon of the Savior during His lifetime (the 'Icon-Fabricated-Without-Easily') and of Icons of the Nigh-Holy Theotokos [Mary] immediately subsequently Him."[37]

Eastern Orthodoxy further teaches that "a clear understanding of the importance of Icons" was part of the church from its very beginning, and has never changed, although explanations of their importance may have developed over time. This is because icon painting is rooted in the theology of the Incarnation (Christ existence the eikon of God) which did not change, though its subsequent clarification within the Church building occurred over the period of the outset seven Ecumenical Councils. As well, icons served equally tools of edification for the illiterate faithful during most of the history of Christendom. Thus, icons are words in painting; they refer to the history of salvation and to its manifestation in concrete persons. In the Orthodox Church "icons take e'er been understood equally a visible gospel, as a testimony to the great things given man by God the incarnate Logos".[38] In the Council of 860 it was stated that "all that is uttered in words written in syllables is also proclaimed in the linguistic communication of colors".[39]

Eastern Orthodox notice the first example of an image or icon in the Bible when God made homo in His own paradigm (Septuagint Greek eikona), in Genesis ane:26–27. In Exodus, God commanded that the Israelites non make any graven epitome; simply soon afterwards, he commanded that they make graven images of cherubim and other like things, both as statues and woven on tapestries. Later, Solomon included nonetheless more than such imagery when he built the first temple. Eastern Orthodox believe these authorize equally icons, in that they were visible images depicting heavenly beings and, in the case of the cherubim, used to indirectly betoken God's presence above the Ark.

In the Book of Numbers[ specify ] it is written that God told Moses to make a bronze snake, Nehushtan, and agree it up, so that anyone looking at the serpent would be healed of their snake bites. In John 3, Jesus refers to the aforementioned serpent, maxim that he must be lifted upwards in the same way that the ophidian was. John of Damascus too regarded the brazen snake as an icon. Further, Jesus Christ himself is called the "image of the invisible God" in Colossians ane:fifteen, and is therefore in one sense an icon. As people are likewise made in God's images, people are also considered to be living icons, and are therefore "censed" along with painted icons during Orthodox prayer services.

According to John of Damascus, anyone who tries to destroy icons "is the enemy of Christ, the Holy Mother of God and the saints, and is the defender of the Devil and his demons". This is because the theology backside icons is closely tied to the Incarnational theology of the humanity and divinity of Jesus, and then that attacks on icons typically accept the effect of undermining or attacking the Incarnation of Jesus himself as elucidated in the Ecumenical Councils.

Basil of Caesarea, in his writing On the Holy Spirit, says: "The award paid to the paradigm passes to the prototype". He too illustrates the concept past saying, "If I indicate to a statue of Caesar and ask you 'Who is that?', your reply would properly be, 'It is Caesar.' When you say such yous exercise non hateful that the stone itself is Caesar, but rather, the name and honor you lot ascribe to the statue passes over to the original, the classic, Caesar himself."[40] And so information technology is with an icon.

Thus to kiss an icon of Christ, in the Eastern Orthodox view, is to prove honey towards Christ Jesus himself, non mere wood and paint making up the physical substance of the icon. Worship of the icon as somehow entirely divide from its epitome is expressly forbidden by the Seventh Ecumenical Council.[38]

Icons are often illuminated with a candle or jar of oil with a wick. (Beeswax for candles and olive oil for oil lamps are preferred because they burn very cleanly, although other materials are sometimes used.) The illumination of religious images with lamps or candles is an ancient do pre-dating Christianity.

-

A adequately elaborate Eastern Orthodox icon corner every bit would be found in a private home.

-

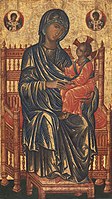

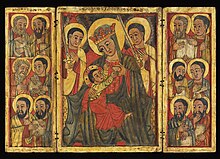

A somewhat disinterested treatment of the emotional subject area and painstaking attention to the throne and other details of the material world distinguish this Italo-Byzantine work by a medieval Sicilian master from works by imperial icon-painters of Constantinople.

Icon painting tradition by region [edit]

Byzantine Empire [edit]

![]()

Of the icon painting tradition that developed in Byzantium, with Constantinople every bit the chief city, we have merely a few icons from the 11th century and none preceding them, in part because of the Iconoclastic reforms during which many were destroyed or lost, and too considering of plundering by the Republic of Venice in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, and finally the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

It was simply in the Komnenian menstruation (1081–1185) that the cult of the icon became widespread in the Byzantine world, partly on business relationship of the dearth of richer materials (such as mosaics, ivory, and vitreous enamels), just also because an iconostasis a special screen for icons was introduced then in ecclesiastical practice. The style of the time was severe, hieratic and distant.

In the late Comnenian period this severity softened, and emotion, formerly avoided, entered icon painting. Major monuments for this change include the murals at Daphni Monastery (c. 1100) and the Church of St. Panteleimon about Skopje (1164). The Theotokos of Vladimir (c. 1115, illustration, correct) is probably the most representative example of the new trend towards spirituality and emotion.

The tendency toward emotionalism in icons continued in the Paleologan period, which began in 1261. Palaiologan art reached its pinnacle in mosaics such as those of Chora Church. In the last one-half of the 14th century, Palaiologan saints were painted in an exaggerated manner, very slim and in contorted positions, that is, in a style known every bit the Palaiologan Mannerism, of which Ochrid's Proclamation is a superb example.

Later on 1453, the Byzantine tradition was carried on in regions previously influenced by its religion and civilization—in the Balkans, Russia, and other Slavic countries, Georgia and Armenia in the Caucasus, and among Eastern Orthodox minorities in the Islamic earth. In the Greek-speaking globe Crete, ruled by Venice until the mid-17th century, was an important center of painted icons, as habitation of the Cretan School, exporting many to Europe.

Crete [edit]

Crete was under Venetian control from 1204 and became a thriving middle of art with somewhen a Scuola di San Luca, or organized painter's guild, the Lodge of Saint Luke, on Western lines. Cretan painting was heavily patronized both by Catholics of Venetian territories and by Eastern Orthodox. For ease of transport, Cretan painters specialized in panel paintings, and adult the ability to work in many styles to fit the sense of taste of various patrons. El Greco, who moved to Venice after establishing his reputation in Crete, is the most famous artist of the school, who continued to utilize many Byzantine conventions in his works. In 1669 the city of Heraklion, on Crete, which at one time boasted at least 120 painters, finally fell to the Turks, and from that fourth dimension Greek icon painting went into a decline, with a revival attempted in the 20th century past fine art reformers such equally Photis Kontoglou, who emphasized a return to earlier styles.

Russia [edit]

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, oftentimes small, though some in churches and monasteries may be as big as a table pinnacle. Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol—the "carmine" corner (meet Icon corner). In that location is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary past an iconostasis, a wall of icons.

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' post-obit its conversion to Orthodox Christianity from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in 988 AD. As a general dominion, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by usage, some of which had originated in Constantinople. As fourth dimension passed, the Russians—notably Andrei Rublev and Dionisius—widened the vocabulary of iconic types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere. The personal, improvisatory and artistic traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Russia earlier the 17th century, when Simon Ushakov'southward painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from Protestant as well as Catholic Europe.

In the mid-17th century, changes in liturgy and do instituted by Patriarch Nikon of Moscow resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists, the persecuted "Old Ritualists" or "Old Believers", continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice. From that fourth dimension icons began to be painted not only in the traditional stylized and nonrealistic mode, but also in a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism, and in a Western European manner very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. The Stroganov Schoolhouse and the icons from Nevyansk rank amid the last of import schools of Russian icon-painting.

Romania [edit]

In Romania, icons painted as reversed images behind drinking glass and set in frames were common in the 19th century and are even so made. The procedure is known as opposite glass painting. "In the Transylvanian countryside, the expensive icons on panels imported from Moldavia, Wallachia, and Mt. Athos were gradually replaced by modest, locally produced icons on drinking glass, which were much less expensive and thus attainable to the Transylvanian peasants[.]"[41]

Serbia [edit]

Trojeručica meaning "Iii-handed Theotokos", the most of import Serb icon.

The primeval historical records almost icons in Serbia dates back to the menstruation of Nemanjić dynasty. One of the notable schools of Serb icons was active in the Bay of Kotor from the 17th century to the 19th century.[42]

Trojeručica pregnant "Iii-handed Theotokos" is the most important icon of the Serbian Orthodox Church and chief icon of Mount Athos.

Egypt and Ethiopia [edit]

Ethiopian Orthodox painting of the Virgin Mary nursing the infant Christ

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and Oriental Orthodoxy also accept distinctive, living icon painting traditions. Coptic icons have their origin in the Hellenistic art of Egyptian Tardily Antiquity, as exemplified by the Fayum mummy portraits. Beginning in the 4th century, churches painted their walls and fabricated icons to reflect an authentic expression of their religion.

Aleppo [edit]

The Aleppo School was a school of icon-painting, founded by the priest Yusuf al-Musawwir (too known as Joseph the Painter) and active in Aleppo, which was then a part of the Ottoman Empire, between at least 1645[44] and 1777.[45]

Western Christianity [edit]

Although the word "icon" is not by and large used in Western Christianity, there are religious works of art which were largely patterned on Byzantine works, and as conventional in composition and depiction. Until the 13th century, icon-like depictions of sacred figures followed Eastern patterns—although very few survive from this early period. Italian examples are in a style known as Italo-Byzantine. From the 13th century, the western tradition came slowly to let the creative person far more flexibility, and a more realist approach to the figures. If only considering there was a much smaller number of skilled artists, the quantity of works of art, in the sense of panel paintings, was much smaller in the Due west, and in most Western settings a unmarried diptych as an altarpiece, or in a domestic room, probably stood in place of the larger collections typical of Orthodox "icon corners".

Only in the 15th century did production of painted works of art begin to approach Eastern levels, supplemented past mass-produced imports from the Cretan School. In this century, the apply of icon-like portraits in the West was enormously increased past the introduction of old chief prints on newspaper, by and large woodcuts which were produced in vast numbers (although inappreciably any survive). They were mostly sold, mitt-coloured, by churches, and the smallest sizes (oftentimes simply an inch high) were affordable even by peasants, who glued or pinned them straight onto a wall.

With the Reformation, after an initial doubtfulness amid early Lutherans, who painted a few icon-like depictions of leading Reformers, and connected to paint scenes from Scripture, Protestants came down firmly against icon-like portraits, especially larger ones, even of Christ. Many Protestants found these idolatrous.[ citation needed ]

Catholic Church view [edit]

The Catholic Church accepted the decrees of the iconodule 7th Ecumenical Quango regarding images. At that place is some minor difference, notwithstanding, in the Cosmic attitude to images from that of the Orthodox. Following Gregory the Peachy, Catholics emphasize the role of images as the Biblia Pauperum, the "Bible of the Poor", from which those who could not read could notwithstanding learn.[ commendation needed ]

Catholics also, however, share the same viewpoint with the Orthodox when it comes to prototype veneration, believing that whenever approached, sacred images are to be shown reverence. Though using both apartment wooden console and stretched canvas paintings, Catholics traditionally have also favored images in the form of three-dimensional statuary, whereas in the East, statuary is much less widely employed.

Lutheran view [edit]

A joint Lutheran–Orthodox statement fabricated in the 7th Plenary of the Lutheran–Orthodox Articulation Committee, in July 1993 in Helsinki, reaffirmed the ecumenical quango decisions on the nature of Christ and the veneration of images:

7. As Lutherans and Orthodox we assert that the teachings of the ecumenical councils are authoritative for our churches. The ecumenical councils maintain the integrity of the teaching of the undivided Church concerning the saving, illuminating/justifying and glorifying acts of God and reject heresies which subvert the saving piece of work of God in Christ. Orthodox and Lutherans, yet, have unlike histories. Lutherans have received the Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan Creed with the addition of the filioque. The Seventh Ecumenical Quango, the 2d Council of Nicaea in 787, which rejected iconoclasm and restored the veneration of icons in the churches, was non office of the tradition received by the Reformation. Lutherans, however, rejected the iconoclasm of the 16th century, and affirmed the stardom between adoration due to the Triune God lonely and all other forms of veneration (CA 21). Through historical research this council has go better known. Nevertheless it does not have the same significance for Lutherans every bit it does for the Orthodox. Notwithstanding, Lutherans and Orthodox are in agreement that the Second Council of Nicaea confirms the christological didactics of the earlier councils and in setting forth the part of images (icons) in the lives of the faithful reaffirms the reality of the incarnation of the eternal Discussion of God, when it states: "The more frequently, Christ, Mary, the mother of God, and the saints are seen, the more are those who run across them drawn to remember and long for those who serve as models, and to pay these icons the tribute of salutation and respectful veneration. Certainly this is non the full adoration in accordance with our faith, which is properly paid only to the divine nature, but it resembles that given to the figure of the honored and life-giving cross, and also to the holy books of the gospels and to other sacred objects" (Definition of the Second Council of Nicaea).[46]

Run across also [edit]

- Analogion

- Christian symbolism

- Early Christian art and architecture

- Holy carte du jour

- Iconoclasm

- Orans

- Podea

- Proskynetarion

- Religious image

- Warsaw Icon Museum

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c "Answering Eastern Orthodox Apologists regarding Icons". The Gospel Coalition.

- ^ "Icons Are Not "Written"". Orthodox History. 8 June 2010.

- ^ Bogomolets O. Radomysl Castle-Museum on the Royal Road Via Regia". Kyiv, 2013 ISBN 978-617-7031-15-3

- ^ Nichols, Aidan (2007). Redeeming Beauty: Soundings in Sacral Aesthetics. Ashgate studies in theology, imagination, and the arts. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 84. ISBN9780754658955 . Retrieved 31 May 2020 – via Google Books.

... ancient religious art can be said to have created, all unconsciously, a pre-Christian icon.

- ^ Michele Bacci, Il pennello dell'Evangelista. Storia delle immagini sacre attribuite a san Luca (Pisa: Gisem, 1998).

- ^ Finney, viii–xii, viii and xi quoted

- ^ Finney, 108

- ^ Veronica and her Material, Kuryluk, Ewa, Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, 1991

- ^ "The Gentle Get out » Council of Elvira". Conorpdowling.com . Retrieved 2012-12-10 .

- ^ "Church Fathers: Letter 51 (Jerome)". world wide web.newadvent.org.

- ^ John Francis Wilson: Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the Lost Metropolis of Pan I.B. Tauris, London, 2004.

- ^ David K. Gwynn, From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Structure of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy [Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47 (2007) 225–251], p. 227.

- ^ Play a joke on, Pagans and Christians, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1989.

- ^ Dix, Dom Gregory (1945). The Shape of the Liturgy. New York: Seabury Printing. pp. 413–414.

- ^ "Is Venerating Icons Idolatry? A Response to the Credenda Calendar".

- ^ a b Robin Cormack, "Writing in Gilt, Byzantine Society and its Icons", 1985, George Philip, London, ISBN 0-540-01085-v

- ^ Excerpted by Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos; this passage is past some considered a later interpolation.

- ^ "Photo". world wide web.avellinomagazine.it . Retrieved 2020-08-08 .

- ^ "Photograph". www.mariadinazareth.it . Retrieved 2020-08-08 .

- ^ "STblogs.org". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-05-07 .

- ^ Margherita Guarducci, The Primacy of the Church of Rome, (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991) 93–101.

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 111, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- ^ Father H. Hosten in his volume Antiquities notes the following "The picture at the mount is one of the oldest, and, therefore, one of the most venerable Christian paintings to exist had in India."

- ^ Cormack, Robin (1997). Painting the Soul; Icons, Decease Masks and Shrouds. Reaktion Books, London. p. 46.

- ^ Belting, Likeness and Presence, Chicago and London, 1994.

- ^ Ernst Kitzinger, The Cult of Images in the Historic period before Iconoclasm, Dumbarton Oaks, 1954, quoted by Pelikan, Jaroslav; The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600–1700, University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- ^ Pelikan, The Spirit of Eastern Christendom

- ^ Patricia Karlin-Hayter, Oxford History of Byzantium, Oxford Academy Printing, 2002.

- ^ M Schiller (1971), Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I (English trans. from German), London: Lund Humphries, ISBN 0-85331-270-two

- ^ (Beckwith 1979, pp. 80–95) Covers all these plus the few other painted images elsewhere.

- ^ De Trinitate 8:4–5.

- ^ Church building History ane:15.

- ^ Belting, Likeness and Presence, University of Chicago Printing, 1994.

- ^ Karlin-Hayter, Patricia (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Printing.

- ^ Mango, Cyril (1986). The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453. University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Leonid Ouspensky, Theology of the Icon, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1978.

- ^ These Truths We Concord, St. Tikhon'south Seminary Printing, 1986.

- ^ a b Scouteris, Constantine B. (1984). "'Never as Gods': Icons and Their Veneration". Sobornost. half dozen: half-dozen–18 – via Orthodox Research Found.

- ^ Mansi xvi. 40D. Run into also Evdokimov, Fifty'Orthodoxie (Neuchâtel 1965), p. 222.

- ^ Meet also: Price, S. R. F. (1986). Rituals and Power: The Roman Royal Cult in Asia Pocket-size (illustrated reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 204–205. Cost paraphrases St. Basil, Homily 24: "on seeing an image of the king in the foursquare, one does not allege that there are two kings". Veneration of the image venerates its original: a similar illustration is implicit in the images used for the Roman Purple cult. It does non occur in the Gospels.

- ^ Dancu, Juliana and Dumitru Dancu, Romanian Icons on Glass, Wayne State University Printing, 1982.

- ^ "[Projekat Rastko - Boka] Ikone bokokotorske skole". www.rastko.rs . Retrieved 2020-05-x .

- ^ Cathedral of the Forty Martyrs: fresco of the Terminal Judgement (Rensselaer Digital Collections).

- ^ Lyster, William, ed. (2008). The Cave Church building of Paul the Hermit at the Monastery of St. Paul in Egypt. Yale Academy Press. p. 267. ISBN9780300118476.

- ^ Immerzeel, Mat (2005). "The Wall Paintings in the Church of Mar Elian at Homs: A 'Restoration Project' of a Nineteenth-century Palestinian Master". Eastern Christian Art. ii: 157. doi:10.2143/ECA.2.0.2004557.

- ^ "The Ecumenical Councils and Authority in and of the Church (Lutheran-Orthodox Dialogue Statement, 1993)" (PDF). The Lutheran World Federation. July 1993. Retrieved x March 2020.

References [edit]

- Beckwith, John (1979). Early Christian and Byzantine Art. Penguin History of Art series (2nd ed.). ISBN0-xiv-056033-five.

Further reading [edit]

- Evans, Helen C. (2004). Byzantium: Organized religion and Power (1261–1557) . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. ISBNone-58839-113-2.

- Evans, Helen C.; Wixom, William D. (1997). The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Civilization of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843–1261 . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-8109-6507-ii.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Icon. |

- "Iconography", at Orthodox Wiki

- Orthodox Iconography, by Elias Damianakis

- "A Discourse in Iconography" past John of Shanghai and San Francisco, Orthodox Life Vol. 30, No. one (January–Feb 1980), pp. 42–45 (via Archangel Books).

- "The Iconic and Symbolic in Orthodox Iconography", at Orthodox Info

- "Icon & Worship—Icons of Karakallou Monastery, Mt.Athos"

- Ikonograph – gimmicky Byzantine icon studio, iconography schoolhouse, and Orthodox resources]

- "Orthodox Iconography" Theodore Koufos at Ikonograph

- "Contemporary Orthodox Byzantine Style Murals" – gallery, at Ikonograph

- Iconography Guide – free eastward-learning site

- "On the Difference of Western Religious Fine art and Orthodox Iconography", by icon painter Paul Azkoul

- "Explanation of Orthodox Christian Icons", from Church building of the Nascence

- "Concerning the Veneration of Icons", from Church of the Birth

- "Holy Icons: Theology in Color", from Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese

- "Icons of Mount Athos", from Macedonian Heritage

- "Icons", from Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

- Icon Art – gallery of icons, murals, and mosaics (mostly Russian) from the 11th to the 20th century

- Eikonografos – collection of Byzantine icons

- My World of Byzantium by Bob Atchison, on the Deësis icon of Christ at Hagia Sophia, and four galleries of other icons

muncietuptionvill.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Icon

0 Response to "Theology of the Icon a Large Number of Works About Sacred Christian Art"

Post a Comment